The "last wild Indian" story

In August of 1911 a starving native-American man walked out of the Butte County wilderness into Oroville and became an instant journalistic sensation. He was identified by UC anthropologists Alfred Kroeber and T. T. Waterman as the last of a remnant band of Yahi people native to the Deer Creek region.

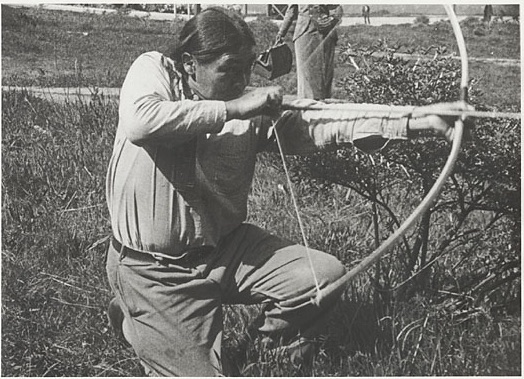

The UC anthropologists immediately went north to Oroville and brought him back to live on the Parnassus campus, giving him the name “Ishi” which meant “man” in the Yahi language. During the next four years, the anthropologists and physicians at UC would learn much from Ishi, as he demonstrated his toolmaking and hunting skills, and spoke his tribal stories and songs.

Newspapers frequently referred to Ishi as the “last wild Indian,” and the press was full of anecdotes referring to Ishi’s reaction to twentieth-century technological wonders like streetcars, theaters, and airplanes. In his writings, Waterman respectfully noted Ishi’s “gentlemanliness, which lies outside of all training and is an expression of inward spirit,” and the records of the time reveal much mutual respect on the part of Ishi and his scientist-observers. Each weekend, hundreds of visitors flocked to Parnassus to watch Ishi demonstrate arrow-making and other aspects of his tribal culture.

Historical Period

1840s: Approximately 400 Yahi people exist in California; total Yana peopleestimated at 1500. 1849: California Gold Rush begins. Ishi’s birth ca 1860. 1865: The massacres of Yahi People begin, 74 killed. 1866: Three Knolls Massacre, 40 killed; Dry Camp Massacre, 33 killed. 1871 Kingsley Cave/Morgan Valley Massacre 30 killed. 1870-1911: Period of Concealment: a remnant band (five to twenty individuals) of Yahi hide in the Mill Creek area. November 10,1908: Surveying party surprises a band of four; Ishi escapes and hides; out of curiosity the surveyors take tools and artifacts from the camp. October, 1910: T.T. Waterman leads an expedition into the Mill Creek area to attempt to find the lost band of Indians, finds “incontrovertible evidence of their existence in a wild state.” No contact made.

August 1911: Ishi walks out of Butte County wilderness into Oroville. September 4, 1911: T.T. Waterman brings Ishi to San Francisco October 1911: Museum of Anthropology opens at Parnassus; over the next six months, 24,000 people visit the museum and watch Ishi demonstrate arrowmaking and firebuilding. November 22, 1911: Ishi hospitalized for respiratory infection; all TB diagnostic tests are negative. December 26, 1911: Ishi hospitalized with bronchopneumonia, photos and casts taken of his feet. September, 1912: Ishi hospitalized three days for abdominal pain. Ishi becomes acquainted with UC Surgeon, Dr. Saxton Pope; they begin archery collaboration. May 1913: Ishi hospitalized two days for back pain. May 1914: Pope does a complete clinical history of Ishi: “No Premonition of Illness.”

August 28, 1915: Kroeber informs T.T. Waterman and Gifford of plans for Ishi’s convalescence: “We have got to handle the case. The physicians go by the book and rule, and it’s up to us to apply our knowledge of the individual and our judgment to their findings and advice. He undoubtedly has had TB since last winter, though for the last 6 months it has been only latent… We must let the doctors get their crack at him, but unless he has really broken I don’t think they’ll find out much… If he gets back to where he was all spring, I believe the same treatment is the only one–reasonable air, exercise and distraction, with every ready tab on the progress of the disease with scales and thermometer. If …the disease continues active even though mild, I suggest sending him preferably to our former watchman…himself a lunger of ten years’ standing; or if he won’t have him, then to the Appersons. Pope has the only right idea, which is to handle him as a person, not as a hospital case….I sail for Europe Tuesday…for about two months then back here. [New York and the Museum of Natural History] September 30, 1915: Gifford replies, “Ishi has improved slowly, but he is a long way from being on his feet. The doctors feel that he will be better off in our building. …the doctors say he is not in condition to move to the country…”

The man who found Ishi

History that makes you perfect